- Home

- Madeleine Roux

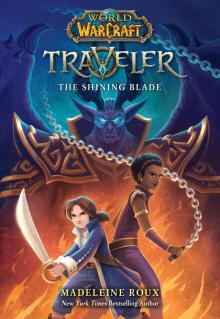

The Shining Blade Page 2

The Shining Blade Read online

Page 2

She glanced back at Aram, who was only a few feet behind. So far, he and Hackle managed best. Hackle’s thickly padded feet and fur insulated him against the relentless heat. Flecks of ash like snow nestled in his mottled fur, and his ever-twitching nose made funny wheezing sounds. Aram’s shoulders drooped, but he marched along without complaint. Makasa’s vigilant eyes swept toward Drella, the dryad. She had cantered over to a withered tree, her eyes filmed with tears, but focused and concentrating. The dryad reached out with one hand, her slender fingers almost touching the blackened bark, and for a moment nothing happened, but then her entire body jolted, a connection of leafy green tendrils snaking between the dryad and the dead tree. Even Makasa was distracted as tiny, new shoots sprang up through the cracks in the bark. Drella shut her eyes suddenly, crying out and then rearing back, and Makasa groaned as she watched the littlest among them begin to tumble off the dryad’s speckled back.

The new life growing on the tree stalled, already smoking in the cruel, hot air.

Makasa, still light enough on her feet, darted back and to the right, skidding through the fine layer of soft ash on the ground, stopping beside the dryad and catching Murky before he could hit the earth.

“Is he all right?” Aram trotted to her side, reaching over to wipe a smudge of dirt off the murloc’s forehead.

“Murky nk blurg mlger.” His huge eyes rolled back, and Drella gasped.

Then she coughed.

“Oh! I thought perhaps I could heal these trees, but my power … I am simply not strong enough yet. And Murky! He is so weak! He really is lightly toasted.” She swept the murloc out of Makasa’s arms. That was just fine with her. Murky, slimy and sticky, wasn’t exactly a treat to hold. Even so, she couldn’t help but share a frown with Aram.

“No,” Makasa murmured while Drella tried to rouse the exhausted Murky. “We can’t stop again.” She turned north and shuddered. Dark clouds gathered, but too low to be rain. It was no natural storm, but some kind of strange, swirling dust formation. Worse, daylight fled, and the high, sharp ridges around them looked like scorched daggers spearing toward the sky. Far-off screeches that only Makasa had seemed to notice grew steadily closer.

Drakes, she thought. Doom.

Behind them, their tracks had vanished, swallowed by the shifting, hot winds that had crammed her eyes full of filth. Makasa wiped at her face and then sighed. After hours of dodging drake nests and fissures of flame, they were all of them caked in ash.

“We can’t turn back,” she addressed their troop. “The Overlook has to be closer than the shore. Besides, what would we do if we turned around?”

Aram shifted his pack, and Hackle tested the air, then gave a mighty snort.

“Hackle carry murloc,” Hackle suggested. “Give break. Hackle strong, not tired yet.”

But Makasa heard the strain in the gnoll’s voice. Gods, they were all struggling. The map she consulted on the airship wouldn’t change shapes no matter how much she wished it would—no, the distance remained the same: two horrid days to make it to the Overlook. The misery of the vale ought to break after the first day, but they still had to make it that far. Drella gently handed the limp and trembling murloc to Hackle, who did his best to pull a flap of leather armor over the poor little creature’s face.

“We have to press on,” Makasa said again. The others nodded, but didn’t move. She looked again to Aram, and he fiddled nervously with the strap of his pack.

As if to prove Makasa right, a chorus of shrieks sliced through the eerie silence of the vale. The shadows grew longer the more they tarried, and Makasa yanked hard on the chain around her chest, pulling it free. She gave it a few experimental swings, swiveling in a circle. The smoldering fires in the vale flickered, playing tricks, but she knew a hungry cry when she heard one. The smaller dragon whelps might have been shy of them during the day, but that advantage would soon be lost when their larger kin took to the skies.

Black drakes. She could already imagine their massive silhouettes sweeping across the moon.

“I hate to say it,” she said, marching to the head of their troop and adjusting the cloth over her mouth. “But that dust storm up ahead might be our best shot. Those drakes can’t carry off what they can’t see.”

“Perhaps I could reason with the drakes!” Drella might have sounded her usual confident self, but even she looked wilted. All the same, she dashed up next to Makasa, stirring the warm earth with her hooves, and Aram, predictably, squared up beside the dryad.

“I don’t think that will work,” Makasa warned. “I doubt drakes are big talkers.”

“You cannot know that. And they have never spoken to someone like me!” Drella shot back.

“Now’s not the time for risking that, Drella! Into the storm,” Makasa called, and not a second too late. Another shrill cry flew across the dust toward them, and Makasa could swear it came with wind beat by cruel wings.

The path curved northeast, the hills crowding closer, the seething whirlwind of the storm hurrying down to meet them. It hit Hackle first, and he gave a gnoll’s hiccupping laugh, not a merry sound, but one of shock. Makasa dropped her head down, spearing into the gritty wind that tore at her face and hands. She refused to drop the chain, convinced that the drakes would follow faster now that the sun dipped so low. Even with her face shielded, she felt her mouth fill with silt, her eyes burning, tears flowing freely down her cheeks. Aram was shouting something to her, but it couldn’t be heard above the roar of the wind.

“What?” she thundered back. Her voice cut at her throat, gritty and dry.

It sounded like he was saying, “A dove!” But that couldn’t be right.

Makasa threw herself to the side, dodging around Drella until she was shoulder to shoulder with her brother. “Say again?!”

“ABOVE!”

Aram ducked his head, grabbing Drella by her lean neck and pulling. The warning came an instant too late, and Makasa’s eyes rolled skyward just in time to see a huge, ebony shadow dive down toward them.

Snarls and gnashing teeth, the acrid stink of sulfur, the drum-like beating of immense, leathery wings … The drakes had come.

She had been right about one thing—it was doom that those nearing screams signaled. But otherwise Makasa had been terribly wrong. The storm had not frightened away the drakes, but only made them bolder. That was the last thought she had before clawed feet tore into her jerkin, shredding her skin, and then, with a roar, she was hoisted into the air.

Makasa heard the others shouting and panicking, her heart hammering in her chest as she struggled to maintain a grip on her weapon. The wind nearly ripped the chain from her hands, but she refused to let go, flicking the end upward to try and startle her kidnapper. Her shoulders pulsed with pain, and she felt blood seeping into her shirt. Maybe that would make her too slick to hold, maybe the storm would win out and take her away from the drake, maybe, maybe, maybe …

The thing was just so bloody strong, and huge, the size of at least four horses. She could hardly think, hardly move, but she tried to jerk the chain up toward the drake again, doing nothing but dislodging a few dry scales. The drake’s wings beat hard, almost useless against the power of the dust storm, and Makasa dared to hope that it would keep them from climbing dangerously high. The flying monsters called to one another, shrill and alarmed, and an instant later Makasa heard a strange sound. A long, low horn echoed across the vale, certainly no roar of a dragon, but of something far more welcome.

She fought to hear anything above the din of the drakes and the whirlwinds churning around them, but after the horn came the sound of heavy feet. Many of them. It came from the north, from their destination, and while the monster hovered, trying in vain to break free of the storm, help came down the mountain. Three large blurs moved at great speed toward them, kicking up their own dust storm. She heard the other drakes and whelps scream and scatter, but her kidnapper hesitated, a fatal mistake.

Makasa flinched, listening to the whistle of a

rrows slicing the air, aimed toward them. More screams from below. Her friends. Another volley of arrows sang toward them, and these connected, peppering the drake carrying her. It shivered and jerked, roaring in sudden agony. Makasa found the strength for one last attempt with her chain, and spun it, arcing it upward. The end looped around one of the arrows sticking out of the drake’s upper leg, hitting its target, and Makasa gave her own cry, pulling as hard as she could.

It worked! she thought, and immediately after: oh no.

Without warning, they were careening toward the ground. Makasa felt the storm slam into them again like a wall, and she closed her eyes, afraid of the impact, afraid of what would come when the winds let go altogether and she could do nothing but fall.

“Can you hear me? Makasa? Makasa …”

This dream had come to her a hundred times before. Her mother called out to her in a voice like a lullaby. She chased after it through darkness so thick it felt like deep ocean. The salt of the sea hung in the air. The char of fire. Her mother’s face, beautiful and blurred, waited just out of reach, receding into the shadows whenever she drew near. Makasa never gave up. She plunged into that clinging darkness, and when she at last broke through, it wasn’t into her mother’s embrace. Instead, she felt her heart plunge—a ghoulish face waited, grinning, a skeleton’s rictus smile and the sweet rot of death draped around it.

“Can you hear me?” it said with its yellow-toothed grin. “Makasa?”

She threw up her hands against it, and sat up, then gasped, watching as Aram tumbled back, holding the spot where her fist had smashed into his cheek.

“Yeah,” he muttered, shaking his head and chuckling in the dirt. “She can hear me.”

Two strange faces stared down at her, both of them belonging to purple-skinned kaldorei. Night elves. Makasa groaned, clutching one shoulder and then the next, but that only brought another nauseating round of pain. She lowered herself back to the ground, finding that she had been deposited on a bed of leaves and soft boughs.

Her armored doublet had been stripped away, her shirt bloodied but not too badly torn. The sleeves had been pulled down to tend to her shoulders, and she sniffed at the greasy balm that had been applied to her wounds. There was a tang to it, almost like salt but not as sharp. That explained her dream. Glancing to her left, she could see the dark horizon of the vale still lingered to the south, which explained the char. But the dust storm had vanished, and the drakes circled far off, drifting back toward the distant shoreline.

“You are quite the fighter,” the taller night elf mused. He had long silver hair, plaited and draped over one shoulder, his feathered helm in hand. He stood and regarded her with one faintly glowing lavender eye; the other was presumably injured, covered by a green leather strap.

“My chain!” Makasa jerked up into a sitting position again, and regretted it. But her pulse raced dangerously—had that damned beast escaped with her beloved weapon?

“It’s here,” Aram assured her, patting a bundle near her feet that included her jerkin. “Iyneath and Llaran brought the drake down. It didn’t stand a chance!”

Makasa snorted at Aram’s enthusiasm. Her young brother beamed up at the two night elves—Sentinels, they called themselves—whose matching longbows arced above their heads. The admiration wasn’t exactly unwarranted, she decided, given that the kaldorei had managed to perfectly pin down a drake in the middle of a dust cloud without skewering her, too. Llaran, the female Sentinel, stood just a hair shorter than Iyneath. They had similarly refined features, long, slender noses and pursed lips that seemed to remain permanently bemused. Brother and sister, she considered, or even twins.

“Aiyell has sent her owl ahead,” Llaran told her. “To alert the Overlook of your coming. They will want to send more guards to manage those drake swarms. They have grown bolder of late.” She knelt and checked the wound on Makasa’s shoulder. It didn’t hurt as much as it ought to, she thought, meaning these night elves had helped them out of more than one bind. Still, Makasa wouldn’t trust them, not while Aram carried that compass of his. Anybody, she knew, could be a spy.

“Thank you,” Makasa said slowly. “We weren’t getting out of that one alive.”

“We weren’t? You weren’t,” Aram teased. “We would’ve run out of that storm just fine.”

She kicked at him, and he laughed.

“Rest now,” Iyneath said in his pleasant and rumbling voice. “Aiyell will soon have a meal prepared, and when you are strong enough, we will strike out for Thal’darah.”

The night elves departed, though there wasn’t much to depart. They had made camp with her compatriots behind a small, hilly outcropping. She cast her gaze around, satisfied. It was a decent spot for a camp, defendable and sheltered. The crueler air of the Charred Vale lifted a little here, and she even saw fresh, green grass poking up among the cracks in the ground. To the west, a few cemetery stones gleamed, a feeble tree growing with a tangle of wild steelbloom at its roots. A fire crackled not far away, the popping sounds rising above the soft murmur of voices. The others. Makasa huddled back down on the makeshift cot, tired but something else. Something more.

“I almost got us all killed,” she said, squeezing her eyes shut. “If those scouts hadn’t found us—”

“You can’t think that way,” Aram replied. He took a dirty-looking rag from his captain’s coat pocket and wiped at his face. She wasn’t sure if it was any cleaner afterward. The soot of the vale had settled in the smile lines around his eyes, and it made him look significantly older than his scant twelve years. For a moment she saw their father, Greydon Thorne, staring back at her. “What choice did we have? If we went back, we would be stuck on the beach and easy pickings for those monsters. The storm was a good decision, Makasa; it just didn’t work out the way you planned.”

“Yeah. And that’s why it was foolish.”

“It worked out, right?” He sighed. “You can’t plan for luck, just hope for it. And now you can brag about surviving a drake. I can’t wait to sketch it.”

“I’d say we’ve earned some luck, too.”

Aram nodded, tucking the rag away. She watched his hand drift near his collar, and she could see him trying not to reach for the compass. Maybe that was why he looked older, because he had that thing around his neck, the symbol of his mission to reconstruct the Diamond Blade, to save the Light, his father’s parting gift to him, weighing him down like an anchor. It was his turn to look distraught, so Makasa shifted and tried not to bump her wounded shoulders.

She lowered her voice. “Do you believe the night elves, about who they are, where they’re from?”

Aram’s eyes glittered in the firelight, and he gazed off toward their troop. Or, more likely, toward Drella. Aram had gotten his first taste of responsibility in caring for the dryad, who, it seemed, was always getting into some form of trouble.

“You think me too trusting, but they didn’t need to help us. They had no idea who we were in that storm. I was yelling at them not to hit you, but who knows if they heard me. I think we can trust them. We just need them to get us as far as the Overlook, then you can be as suspicious as you like.”

She nodded. That suspicion wouldn’t drop, not even if that stinky healing balm of theirs could magically disperse the dark cloud over her head.

“I’m glad you made it,” Aram said, pushing up to his feet. “Don’t worry about the storm, Makasa; you still made the right call. Who knows if we’d have made it here on our own. Now get some sleep. I can’t see the back end of this place fast enough.”

Makasa gave him a thin smile, watching him go, then settled down into her leafy bed. Don’t worry about the storm. How? How could she not worry? How could she ignore the storm ahead of them, not one of dust and ash, but a storm of men and steel and cold, terrible vengeance? Malus might be off their back for the moment, but she had no doubt he would show his nasty face again. They could run from him, but he didn’t seem the type to give up easily.

Sleep wou

ldn’t come, but Makasa closed her eyes anyway and tried her hardest not to hear the distant drums of war.

Aram’s legs nearly gave out as they crested the final hill and reached their destination: Thal’darah Overlook. The second day’s march had been less hot, surely, but not necessarily less arduous. The Charred Vale came with plenty of dangers, but once they broke away from the bleak, smoky ruin of the vale, the terrain rose steeply. The way around Battlescar Valley was almost entirely uphill. But there were trees, at least, living, not-on-fire trees with canopies the color of emerald jewels. The lushness stood in stark contrast to the clear-cut war zone of the valley itself, where the Alliance and Horde remained locked in conflict. Eagles looped overhead, crying to one another, the sound so sharp it could pierce straight through the mountains. Rams scattered at their approach, encouraging signs of life after so much brittle, black earth.

The Sentinels walked alongside their mounts—large, pearl-bright moonsabers that managed the steep hills with practiced ease. Murky relaxed on one of the saddles, comically tiny on such a giant creature. Makasa, of course, still injured, rode on Iyneath’s striped saber, her mouth jammed shut in a firm and ungrateful line.

She did smile a bit whenever the night elf scout loped up to walk beside her and inquire about her health.

Hackle, of course, stubbornly declined to ride, and Drella was already swift and steady with her fawn legs. Aram let Aiyell go on ahead, considering he felt good enough to make the journey on foot. And, if he were being completely honest, he wanted to spend the remainder of the march at Drella’s side. Their journey to the Overlook was to undo the magical bond they had shared since her very recent birth, and Aram could admit to himself that he was nervous about the process. Would he feel different? What if it made her indifferent toward him, or even cold?

Asylum

Asylum The Warden

The Warden The Bone Artists

The Bone Artists Allison Hewitt Is Trapped

Allison Hewitt Is Trapped Court of Shadows

Court of Shadows The Scarlets

The Scarlets Escape From Asylum

Escape From Asylum The Shining Blade

The Shining Blade Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft: Shadowlands)

Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft: Shadowlands) Salvaged

Salvaged Sadie Walker Is Stranded

Sadie Walker Is Stranded Catacomb

Catacomb Reclaimed

Reclaimed Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft

Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft Tomb of Ancients

Tomb of Ancients