- Home

- Madeleine Roux

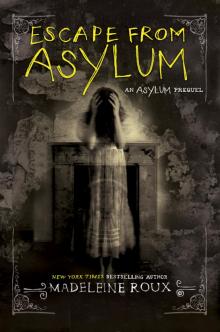

Escape From Asylum

Escape From Asylum Read online

DEDICATION

For the entire Asylum team at HarperCollins

and for fans of the series, old and new.

EPIGRAPH

“I am not an angel,” I asserted; “and I will not be one till I die: I will be myself.”

—CHARLOTTE BRONTË, Jane Eyre

I am not made like any of those I have seen. I venture to believe that I am not made like any of those who are in existence. If I am not better, at least I am different.

—JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Photo Credits

Back Ads

About the Author

Books by Madeleine Roux

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

He hadn’t wanted to be the first. Even the silence of this room sounded like screaming, the scrape of a footstep or the shrill cry of his own doubts in his head, magnifying until he was deafened. It was a good thing to be the first, the warden had assured him. It was an honor. After all, the warden had been waiting for him—for the right person—for such a very long time. Wouldn’t Ricky just be a good boy and cooperate? This was special. To be the first, to be Patient Zero, was a privilege.

But, still, he didn’t want to be the first. This room was cold and lonely, and somehow he knew in his marrow, in the wellspring of his humanity, that to be Patient Zero was bad. Very bad.

To be Patient Zero meant losing himself, not to death, but to something much worse.

Brookline, 1968

Three weeks previous

They brought him silently into the little room. Ricky had been down this road before, only the last time it was at Victorwood in the Hamptons, and he had gone willingly. This was “retreat” number three. It was starting to get annoying.

He hung his head, staring at the floor, putting on the performance of a lifetime. Did he feel remorseful? Not even a little bit, but he wanted out of this place. Brookline Hospital. It might have been a loony bin, but it sounded as pompous and stupid as the retreat centers. He didn’t want anything to do with it.

“I need to see my parents,” he said. Talking made them grip his arms more tightly. One of the orderlies pulled a restraining mask into view, and Ricky didn’t need to put on an act to look shocked. “Whoa, hey, there’s no need for that. I just want to talk to my mom. You gotta understand, there’s been some kind of mistake. If I could just talk to her—”

“Okay, kid. Sure. A mistake.” The orderly chuckled. He was taller and stronger than Ricky, and bucking against him was futile. “We don’t want to hurt you, Rick. We’re trying to help you.”

“But my mother—”

“We’ve heard that one before. A thousand times.”

He had a nice voice, this orderly. Gentle. Kind. It was always like that—sweet voices saying sweet things, covering up dark, mean intentions. Those voices wanted to change him. Sometimes he was even tempted to let them.

“I need to see my parents,” he repeated calmly. It was hard to sound anything but terrified when he was being hauled into a cell in a place he didn’t know. A cell in an asylum. “Please, just let me talk to them. I know it sounds ridiculous, but I think I really can make them understand.”

“That’s all over now,” the orderly said. “Now we’re going to take care of you. Your parents will come get you when you’re feeling better.”

“Warden Crawford is the best,” the other man said. His voice was just as warm, but his gaze was cold as he stared at—through—Ricky. Like Ricky wasn’t there at all, or if he was, he was just a speck of dirt.

“He really is the best,” the taller orderly added mechanically.

Ricky fought them at that. He had heard those words before, about other doctors, other “specialists.” It was code. It was all code, everything these people in “resorts” and hospitals said. They never said what they really had in mind, which was that he would never get out, never be free, until he became a different person altogether. The taller, stronger orderly on his right swore under his breath, struggling to hold on to Ricky’s arm and reach for something out of Ricky’s view.

The room was cold, chilled from the spring rain outside, and the lights were too bright, bleached and pale like the rest of the room. The outdoors had never felt farther away. Maybe it was just a few feet to the wall, and then a few inches of brick, but the free air may as well have been on the other side of a mile of concrete.

“This is your choice,” the orderly said with a grunting sigh. “You make the choices here on how we treat you, Rick.”

Ricky knew that wasn’t true, so he fought harder, tossing his weight from side to side, trying to smash his forehead into one of them and break their grip. Their voices became far-off almost the second the needle slid into his arm, pricking harder than usual, biting deep into the vein.

“I just want to see them,” Ricky was saying, crumpling slowly to the linoleum. “I can make them understand.”

“Of course you can. But you should rest now. Your parents will be back to see you before you know it.”

Soothing words. Nonsense. The details of the room blurred. The bed and the window and the desk all became similar blobs of milky gray. Ricky let himself go fully into the dark, the oncoming numbness almost a relief from the knot of fear and betrayal winding tight in his gut.

Mom and Butch must be already on the road back to Boston. Long gone, long gone. He’d always talked his way out before, and he knew he could do it again if he just had a minute alone with his mother.

“He’ll be all right here, won’t he?” his mother had asked. The Cadillac rolled smoothly up the hill to the hospital, rain beating relentlessly, rhythmically, like tiny toy soldier drums on the windows. “It doesn’t look anything like Victorwood . . . Maybe this is too extreme.”

“How many more times, Kathy? He’s a freak. Violent. He’s a goddamn—”

“Don’t say it.”

It had felt like a dream then, but it felt even more like one now. At first he’d been so sure they were just taking him back to Victorwood, a home for “wayward” boys like him. The staff there were chumps, pushovers, and as soon as he’d had enough of the place, it had taken only a few tearful calls to get his mother racing up the manicured drive, her own eyes filled with tears as she welcomed him into a hug. But they hadn’t been taking him to Victorwood this time. Somewhere along

the way they had turned off, changed course. That Next Time Will Mean Real Consequences moment that Butch liked to reference was finally upon them.

Damn. He shouldn’t have let himself get caught with Martin like that. Butch had finally made good on his threats. The long, angry car ride to the hospital, to Brookline, had been punishment enough, and the whole time Ricky was thinking they wouldn’t really do it. They wouldn’t really commit him.

And now here he was, slipping into unconsciousness far away from home, with two strangers hauling him onto a thin mattress and his last clear thoughts: They did it. This time they really did it. They’re locking me up and they’re not coming back.

He stared at the ceiling for hours and hours, his hands folded tightly over his stomach. His voice felt scratchy from yelling at the orderlies and then, when that hadn’t worked, from humming to himself to try to stave off some of the anxiety. Now he was quiet. The tips of his fingers were so cold, he worried they might just freeze and grow brittle and break off.

That cold had set in the second they came through the doors of the hospital, and it had been his first warning. The yard surrounding Brookline was pretty and well-kept, a sturdy black fence the only indication that the freedom to come and go depended on your status as patient or parent. Brown brick buildings chased along in a U shape next to the hospital. They stood out because they were of a totally different construction than the hospital, dark and old and collegiate. Disheveled young men in sweater vests and corduroys ambled from one building to the next—students preparing to leave for their summer vacations, Ricky would later learn.

Next to those old buildings, Brookline was pure white. Clean. Even the grass had been clipped to a perfectly even height. It had felt fake under his shoes, he remembered that. And there were patients outside in the garden, backs bent, meticulously deadheading the flowers and pruning the hedges while orderlies in crisp uniforms looked on.

It was all pristine and picture-perfect, until you stepped inside, and that cold hit you like a jolt of electricity.

Drowsy as he was, Ricky was certain that he would never get a wink of real rest in this place, not even if they gave him another one of those sedative shots. He kept nodding off and snapping awake again, sure that someone was on the other side of his door, listening in. And his uneasy sleep was broken by a sudden scream in the night. (He assumed it was night—it was difficult to tell in the shuttered cell.)

His limbs were leaden as he pushed into a sitting position. The scream came again, and then again, forcing him fully awake. He drew up and shuffled to the door, pressing himself against the frigid surface. Ricky’s hand slipped lower, coming to rest on the handle; he was shocked when it gave under that little bit of pressure. This couldn’t be. He wouldn’t be allowed to wander the halls of Brookline alone. He could tell from his strong-armed welcome that this wasn’t that kind of place. Had the orderlies screwed up and forgotten to lock him in? It was dark and still in the hallway, with no nurses or orderlies in sight, no other patients, no signs of life whatsoever except a thrum like a heartbeat that drummed low and slow from beneath his feet. Maybe it was the pipes or an old-timey furnace, grumbling below like an ancient, slumbering beast. The root of the building. Its core. The living, beating heart of the asylum.

Ricky wandered down the corridor to the staircase, his bare feet as icy-cold as the floor. A milky light filled the whole place, illuminating the steps as he padded down to the first-floor landing. The beating heart called to him, steady, and he followed. He didn’t feel safe, exactly. More like reckless. What could they do, kick him out? It wasn’t his fault those idiots had left his door unbolted.

Also—and he knew this was weird—the deep bum-bah-bum of the asylum’s heartbeat gave him courage. It almost felt comforting.

It wasn’t until he reached the lobby that his anxiety returned. He had sat here just hours earlier watching Butch fill out the paperwork while his mother wept.

“Won’t you miss me?” he had murmured, giving his mom huge, childlike eyes.

“Honey . . .” She’d almost gone for it, her lip quivering as she stared at him.

“No, not this again.” Butch had finalized it, broken the spell. And Ricky hated him for it.

Now he could feel the dread and the disbelief of that moment rise up harder and stronger, blasting over him like a wave intent on drowning him. He hurried over to the doors that led outside, thinking for a wild second that he’d be better off making a break for it than trying to get ahold of his mom on the phone, but his luck from before ran out—these were definitely locked.

The heart—or the furnace, whatever the hell was making that noise—called more insistently, and he followed once more, but reluctantly this time. “Nowhere to Run” came to mind: the song, the idea. The sound that was emanating from the basement was like the baseline of that song, climbing, driving, dark, and infectious.

Nowhere to run . . .

He was in a part of the asylum he didn’t recognize. That wasn’t exactly a surprise. He hadn’t even been here a full day. The lobby was behind him, and ahead, offices and storage rooms lined a narrow hall that disappeared into a yawning mouth of darkness. An arch. An arch that led down.

So down he went, into the colder and colder depths, feeling the rough stones on the walls, smelling the wormy, wet-earth scent that permeated the basement. The stairs seemed to go on forever, and that steady bum-bah-bum roared louder, reverberating until it was part of him, interwoven with his dread, interwoven with the brick and mortar itself. The pipes rattled, creaked, sudden taps inside of them making him wonder if they were about to burst open any second.

Searching. He was searching now, he realized, desperate to find not a phone or an exit but the source of the heartbeat.

Ricky followed the drumming all the way to a long, tall corridor, the ceiling so high above him it may as well have been empty sky. Something scratched at his back, but when he turned to look, there was nothing there. That’s when he realized he must be dreaming—when what felt like sharp human nails scored through his shirt and burned against his skin, and still nothing was there. He was alone in the hall.

He gritted his teeth against the pain and pressed on toward the heartbeat, passing windowless doors on either side of him that were shut and locked. In the nightmare he knew they would be, but he tried each one anyway. He was suddenly sure that the screaming he’d heard earlier had been coming from this hallway. That someone behind the far door on the right had been crying out so loudly that he could hear it all the way in his room, and the heartbeat had been guiding him straight to the source.

And when he reached the final door on the right? It was open like his. More negligence, surely. He had to go inside, escape the claws scraping at his back and find the heartbeat thundering in his ears. It was his own heartbeat now, his own pulsing fear.

He stopped outside the door and peered in, the scratching nails inside him now, tearing up his stomach and crawling up his throat. There was no scream and no heartbeat, just silence. Then he saw her. A little girl stood in the empty room, her nightgown tattered and soiled. She turned a slow circle, around and around, but every angle Ricky caught was just long, dirty hair.

There was no face beneath the hair but somehow he felt her eyes. Her eyes were there, watching, measuring . . . He was part of this place now. He had been seen.

He was feeling more like himself by morning, rising with “Nowhere to Run” stuck in his head. It was all just an anxiety dream, he decided. There was no way he had actually left his room in the middle of the night.

Just to make sure, he checked the bottoms of his feet. Clean. That was a bigger relief than he wanted to admit.

It was back to plan A: finding a telephone. His parents—or at least his mother—would return for him and soon. She couldn’t live without her sweet little Baby Bear. She would come back for him, with or without Butch, because she was too weak and fragile not to. That wasn’t an insult, it was just the truth. She couldn’t handle her life

without him, not daily decisions, not major responsibilities, not any of it.

And damn. He had almost gotten her, there in the lobby, but Butch had had to ruin it. It was why she had remarried so soon after his real father disappeared. After a year, the courts granted her a divorce based on “abandonment” and Butch was already in their lives by then, like he was just chomping at the bit, waiting to take his dad’s place. She couldn’t be on her own. She couldn’t be accountable for anything. Ricky didn’t know if he hated his mother, but he certainly didn’t like her.

Still. Blood might be thinner than water, in his opinion, but it would win him his freedom in the end.

Soon he would be back in Boston, back in his room, surrounded by his posters of Paul and John, surrounded by his clothes and his things, his books and his baseball cards. He’d probably even get the Biscayne back—his real ticket to freedom, which he’d barely had time to take advantage of before this string of glorified time-outs.

Ricky could already picture it: windows down, music up, the spring wind carrying the glorious scent of hamburgers and hot dogs sizzling on dozens of suburban grills. . . . Mom at least had let him have one last hamburger yesterday before they made it here, but Butch had refused to turn the radio to anything but baseball results.

A short, shy knock came at the door. Ricky sat up in bed and then swung his legs over the edge, running both hands through his rumpled hair as the door opened and a kind-faced, red-haired nurse stepped inside.

“Hello? I’m not interrupting anything, am I?”

Ricky snorted, standing and leaning against the bed. “Is that what passes for a joke around here?”

She wasn’t pretty, necessarily. More like harmless. Clean. And about as sharp in the corners as an origami crane. She stared at him, obviously bewildered.

“Oh. No. I wasn’t making a joke.” She held her clipboard tight to her chest. “I’m Nurse Ash, and I’ll be overseeing your care here at Brookline.”

“Ash. Nurse Ash. Huh. That’s a fittingly macabre name for this charming little dungeon.”

Asylum

Asylum The Warden

The Warden The Bone Artists

The Bone Artists Allison Hewitt Is Trapped

Allison Hewitt Is Trapped Court of Shadows

Court of Shadows The Scarlets

The Scarlets Escape From Asylum

Escape From Asylum The Shining Blade

The Shining Blade Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft: Shadowlands)

Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft: Shadowlands) Salvaged

Salvaged Sadie Walker Is Stranded

Sadie Walker Is Stranded Catacomb

Catacomb Reclaimed

Reclaimed Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft

Shadows Rising (World of Warcraft Tomb of Ancients

Tomb of Ancients